Writing Systems and Language

written by Anthony Sainez

published 11 April 2020

Speech comes naturally, but writing does not.

In 2018, around 32 million American adults were illiterate. In 2018, there were also 327.2 million Americans living in the United States, which means that around 9% of Americans were illiterate at the time. Even in literate societies, writing does not come naturally.

In fact, writing is a development that came relatively recently when compared to the advent of human language. Writing has only really developed around five thousand years ago, with the earliest being Mesopotamian cuneiform. Most languages are not written, even today.

But as different writing and speech are, they still share something in common: speech shares an arbitrary link between sound and meaning, and writing shares an arbitrary link between symbol and sound. Linguists call the set of conventions for writing down language it's orthography, and they can be grouped into two basic types.

Types of Writing

Logographic

In a logographic writing system, symbols (logograms) represent actual morphemes or even entire words.

It's the oldest type of writing, going all the way back to Ancient Mesopotamiam cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs and early Chinese characters.

Letters

continue to fall

like precise rain

along my way.

Nearly all writing systems today are part logographic in that they make use of abbreviations like &, %, $, or even numbers like 1, 2, 3, and the rest. One can even say that logographic systems can even be read independently from their original language, so long as you understand the meaning.

ふるいけや

かわずとびこむ

みずのおと

Phonographic

In a phonographic writing system, symbols represent syllables or phonemes. There are two categories of phonographic writing systems— syllabic and alphabetic.

Syllabic

Perhaps the most commonly known example of a syllabic writing system would be Japanese hiragana, each of which represent a single, discrete syllable. A set of syllabic signs is called a syllabary.

Alphabetic

In an alphabet, signs represent consonant and vowel segments, and among alphabets you can have two distinctions: abjads and abugidas.

Abjads and Abugidas

In an abjad writing system, like in Arabic and Hebrew, vowels are either completely absent or are optionally expressed with the help of something called a diacritic.

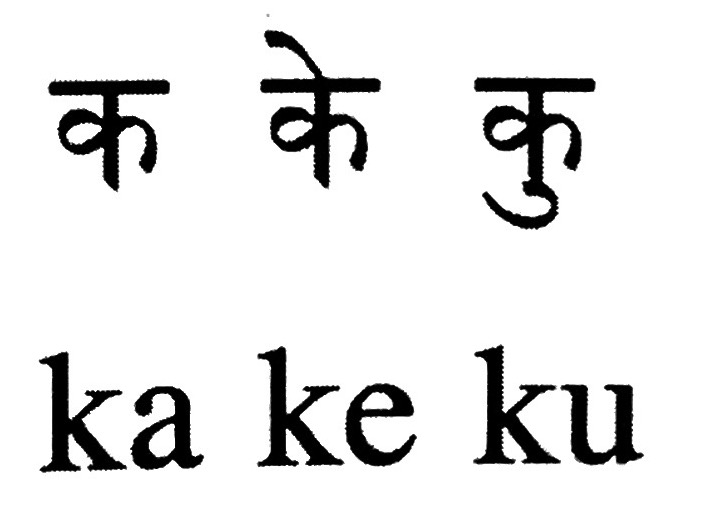

In an abugida writing system, all vowels are represented. But, they are marked by diacritics or modifications to the consonants.

History and Evolution of Writing

The historical record is often divided into two parts: before and after written records (and therefore, writing at all). So, what are the first records of writing?

It all starts with the desire to share information visually. This idea can be traced all the way back to ancient cave paintings in France. It can be said, then, that pictograms were the precursors of writing. A pictogram represents an image of an object, like the silhouette of an ox or grains of wheat, but abstracted. But these sorts of things don't convey sound— it's simply memetic.

In Ancient Mesopotamia, archaeologists have studied clay tokens used for accounting purposes. These are the two most notable examples. However, the first real writing occurs around 5,000 years ago with the advent of cuneiform— writing on clay tablets. Though writing in clay seems awful and unwieldy, it's actually quite lucky that the Mesopotamians wrote this way since it ensures preservation. If writing emerged earlier than cuneiform, but using a different material, it's very likely such an artifact succumbed to time and was destroyed before historians could recover it. As such, cuneiform is the world's first writing system that we have a record of.

Cuneiform

Cuneiform is logographic, but it started out as pictograms that were rotated and moved around for the ease of scribes and scholars at the time.

A drawing of a grain would get simpler and therefore more abstract over time in order to speed up the writing process.

Priests, who used the records to run massive stockpiles in ancient temples, learned to read from top to bottom— like a scroll.

But scribes preferred writing from left to right instead of top to bottom because the chance of pressing your hand down on the wet clay and destroying the tally marks was reduced.

So, the scribes compromised and rotated the characters 90 degrees, so priests could just turn the tablet to read, further abstracting the characters for writers.

Phonographic writing comes after, made possible by the rebus principle. The rebus principle allows a sign to be used for anything with the same pronunciation as it was originally intended. For example, because they were pronounced the same, the symbol for 'reed' could also mean 'reimburse.' Humans are able to cope with this ambiguity and can normally make out what the writer's intention was with some context. Given all that, the Sumerians were able to vastly shrink their set of symbols, making learning how to write much easier. The Sumerians also were able to record things that can't be directly depicted by a pictogram or a logogram— concepts like love and life, given they were pronounced the same as something already concrete.

The Alphabet

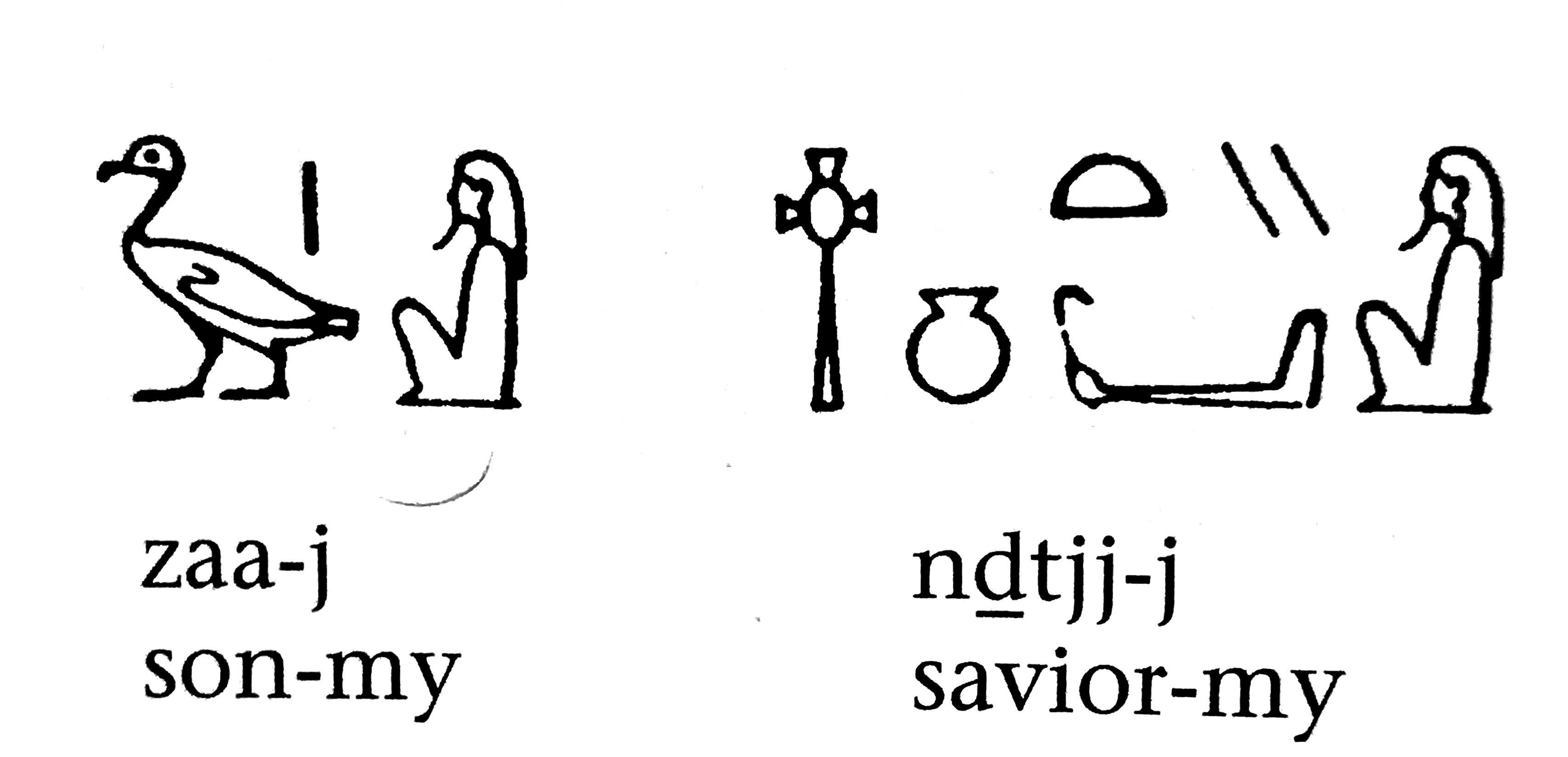

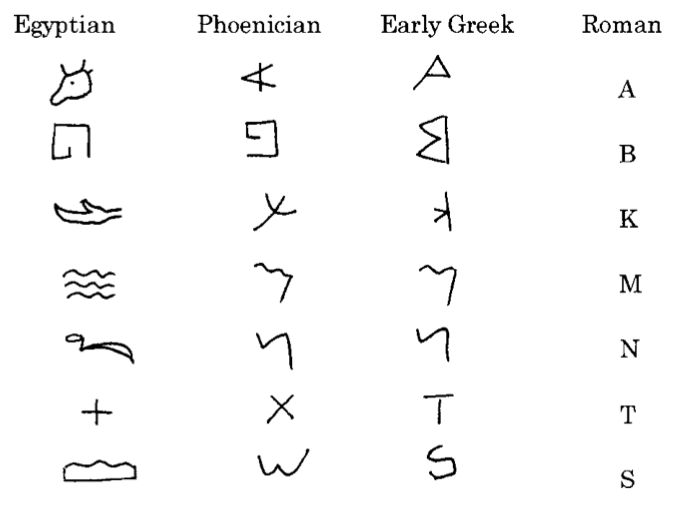

Meanwhile, the Egyptians were working on hieroglyphics. Similar to early Sumerian, they were first pictograms— but the writing system eventually became a mixed bag of phonographic and logographic symbols. The Egyptians also took advantage of the rebus principle in a way similar to the Sumerians, but they took a step further: symbols could represent individual consonants! Linguists call this acrophony.

Picture is from Contemporary Linguistics (O'Grady).

Referenced in The Study of Language (Yule), but originally from Egyptian Hieroglyphics (Davies).

Building off of this mixed bag that is hieroglyphics, the Phoenicians created the letters and symbols that the Greeks later built off of. They developed it into the very first actual alphabet. Fun fact, the first Greek originally written boustrophedon ('as the ox turns'), meaning the lines alternated from which direction they were written. For instance, if the first line was written from left to right, the next line would be written from right to left, as the ox turns!

After the Greeks, the Romans acquired their alphabet and made changes, spreading the writing system all across the empire. When the empire collapsed, it isolated many language communities which then developed apart from each other,

much like how new species of animals evolve when geographically separated. While these languages may have modified sounds or gotten more or less complex, the writing system is much slower to change thanks to education.

Constructed Writing Systems

The Cherokee Syllabary

Let's take a detour and fast forward a bit— only about 4,700 years— to around 1809 in America. We're going to go over some cool stories in linguistics.

Cherokee at the time had no writing system, like many languages today and throughout all of history. That was until a man named Sequoyah decided to invent one for it. After years of arduous experimentation, originally starting with a pictographic system, Sequoyah created on a syllabary of 85 characters.

Sequoyah, along with his daughter, began to spread his writing system around the language community. The Cherokee Phoenix, a bilingual national press, Christian texts and even laws were written in this syllabary.

Literacy rates grew quite rapidly thanks to Sequoyah's invention, and Sequoyah's efforts have had a lasting impact on the Cherokee community even today.

from Wikipedia user Kaldari

Hangul

This event of a single person— Sequoyah in this instance— inventing a writing system is not singular. 367 years earlier in 1440, Sejong the Great created Hangul, the Korean writing system in use today.

Koreans at the time used something called hanja, which was essentially a borrowing of Chinese characters. However, Korean and Chinese are very different languages, and this made using and learning hanja very difficult. Subsequently, the literacy rates at this time were not high. Some scholars would point out the fact that it is not in the interests of monarchs, kings and autocrats to educate the masses, and that King Sejong was frustrated by the systemic and widespread illiteracy in his kingdom.

As the story goes, Sejong employed a group of scholars who he called the Hall of Worthies (Jiphyeonjeon) to create a new alphabet part with emphasis on accessibility and the concept of duality (specifically vowel harmony and yin and yang). The project was a success: Sejong and his Hall of Worthies published and printed the Hunminjeongeum, literally "The Proper Sounds for the Instruction of the People." Hangul remains an incredibly accessible writing system that remained mostly intact from its conception.

This image is courtesy of the Bank of Korea. Please do not print.

Orthographies for Constructed Langauge

Writing systems extend even to fiction— famously so! In fact, creating a writing system is some of the most fun a linguist can have. Many hobbyists spend lots of time creating languages (conlangs) and coming up with writing systems that fit such machinations. Perhaps the most famous example of this would be the languages featured in The Lord of the Rings, written by J. R. R. Tolkien.

One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.

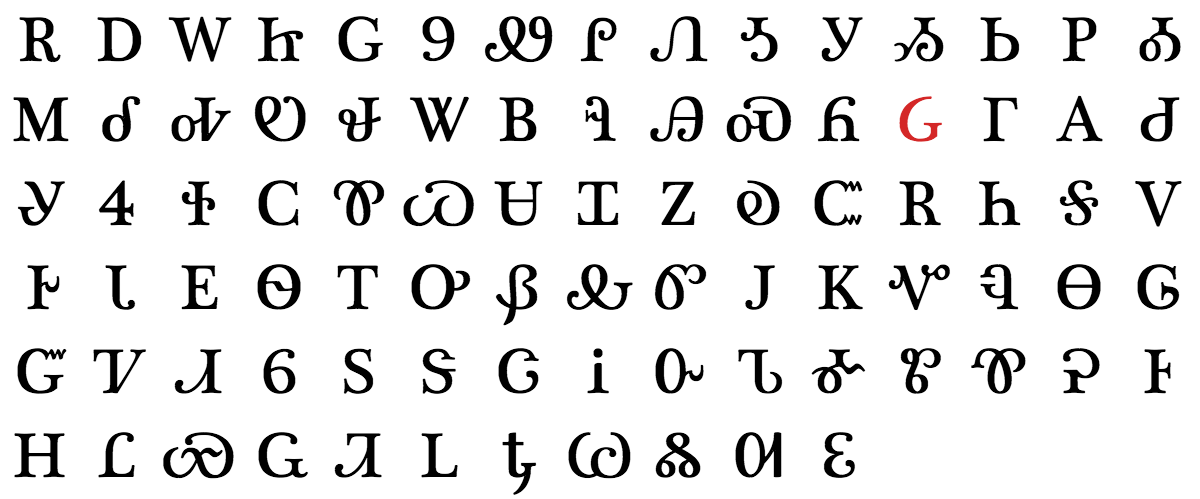

Tengwar, an alphabet Tolkien came up with, is a good example of a constructed writing system. Perhaps best known for being used to inscribe a pivotal plot element (the One Ring) in his novels, tengwar has an entire fictional history attached to it.

A bit of trivia: Tolkien was a linguist of the historical variety, more specifically a philologist— that is, he studied language in historical sources. Philology is a kind of ancestor to a specific subset of modern linguistics,

similar to how "natural philosophy," studied by the likes of Aristotle and Plato, was a precursor to modern natural science.

The creation of orthographies for constructed languages can be a creative outlet for many, and an interesting puzzle or thought experiment at the same time. Some methods of communication present unique challenges for writers and readers.

Tactile Writing Systems

Initially, we talked about how writing systems originated as ways to convey information visually. But there exists writing systems for those with visual impairments too. Of course, the one that jumps to mind immediately is Braille, but there are others. It is probably most productive to examine the whole story.

Braille gets its namesake from Louis Braille who invented the writing system. Louis Braille blinded one eye when he was three, and the other went blind from infection due to the initial injury. In 1821, Braille learned of "night writing," which was originally intended for military communication. Night writing was a code of dots and dashes embossed into thick paper, which could be interpreted entirely by the fingers, theoretically letting soldiers share information on the battlefield without having light or needing to speak. Night writing flopped and never saw any practical use, but the idea stuck with Braille.

By the time Braille was 15, his orthography was nearly complete, and when he was 20 he published "Procedure for Writing Words, Music, and Plainsong in Dots." At the time, the system used dots and dashes, the latter of which he later dropped as they were difficult to distinguish. After constant expansion and many modifications, Braille was able to even express music and mathematical symbols.

By this time, Braille was a professor at the French Royal Institute for Blind Youth. Sadly, he succumbed to tuberculosis at the age of 43. The institute adopted his writing system posthumously after petitions from students.

The War of the Dots

After Braille came Boston Line Letter, which looked like whole letters embossed into paper.

Meanwhile, William Bell Wait at the then New York Institution for the Blind was simultaneously developing his own writing system: New York Point. Initially, he encouraged other schools to make use of Braille's system, but they refused— so he went and made his own.

Braille did not account for the frequency of occurrence of a letter. For instance, the letter 't' occurs more often than 'a' in many languages, yet 't' used more dots than 'a,' which sometimes meant books could get incredibly

bulky.

Enter Joel W. Smith, who sought to fix that problem by creating American Braille. Keep in mind that each of these systems are distinct. Now, you can see the development of writing systems for the blind was quite a mess!

After some advocacy from Hellen Keller, there was finally a consistent writing system for the blind, the one we still use today: Standard English Braille, or Grade 2 Braille.

The various tactile writing systems developed for blind readers have all been alphabetic in nature.

Exploring the tactile orthographies gives us insight into the world of the blind and living with disability. In fact, the choice of a writing system has a noticeable impact on the learnability depending on the reader. Research shows

that the congenitally deaf— that is, those who are born deaf— struggle with phonographic (specifically alphabetic) orthographies. This could be because their disability prevents them from accessing the phonological systems in the

brain that others might have.

Writing is humanity's greatest technological achievement. It enabled us to share information across generations and allowed us to watch and learn from our past. It is a priority that we strive towards higher literacy rates— the ability to read is a gift unparalleled and leads directly to education and empowerment.

Sources and resources

Walker, W., & Sarbaugh, J. (1993). The Early History of the Cherokee Syllabary. Ethnohistory, 40(1), 70-94. doi:10.2307/482159

Roth, G. A., & Fee, E. (2011). The invention of Braille. American journal of public health, 101(3), 454. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.200865

Irwin, R. B. (1933). The War of the Dots. New York: American Foundation for the Blind.

Yule, G. (2020). The Study of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108582889

Dechaine, R.-M., Burton, S., Déchaine Rose-Marie, & Vatikiotis-Bateson, E. (2013). Linguistics For Dummies. Mississauga: John Wiley & Sons.

The History of Writing - Where the Story Begins - Extra History. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HyjLt_RGEww&t=1s

Liberman, M. (n.d.). Reading and Writing. Retrieved April 11, 2020, from https://www.ling.upenn.edu/courses/Fall_2003/ling001/reading_writing.html

Davies, W. (1987) Egyptian Hieroglyphics. British Museum/University of California Press. Referenced in The Study of Language.