Phonetics

Anthony Sainez

published 27 July 2020

Phonetics is the study and classification of speech sounds, and linguists who study phonetics are called phoneticians. The word phonetics is derived from the ancient Greek word phōnē, which means 'sounds' or 'to speak'.

Individual speech sounds, like [b] or [k] are called phones— not to be confused with actual phones, like the one in your pocket! There’s a finite amount of them, since we use our vocal tract to make noise and it’s

not capable of producing an infinite number of noises.

Phonetic Transcription

Since the sixteenth century, we have made efforts to use a universal system for writing down sounds. Today, we use the International Phonetic Alphabet, which is commonly abbreviated to IPA.

You can find the alphabet here.

Normally, the transcription is indicated by brackets: the “b” sound in “buy” is denoted by [b] The IPA represents speech in segments, like the individual [b] phone in

the previous example.

Why study phonetics?

Researchers from many disciplines use the tools of phonetic analysis.

Phonetics is used to help develop technology like Siri or Google Assistant, not only in their capacity to speak but also in their ability to hear! These technologies are relied upon by many people from people who simply have their hands full to people with severe vision disabilities, like blindness.

Making Noise

Sound is basically just airwaves vibrating really fast in your ear. So, in order for us to make speech sounds, we have to vibrate air really fast. As you already know, we have a special place on our body just for this: the larynx,

located at your Adam’s apple. It houses the vocal folds (sometimes referred to as cords) which you use to manipulate the air your lungs provide into speech sounds, and it’s also made out of cartilage.

As air flows outta the lungs and up the trachea (sometimes called windpipe), and into your larynx. As it goes through the vocal cords, which is also called the glottis, different glottal states are

achieved.

Glottal States

The two glottal states are: voiceless and voiced.

When the vocal folds are pulled apart and air passes directly through without a lot of interference, it produces voiceless sound.

Try this: feel your vocal cords as you say the first sound in the word “shy.” Now try it with “bird.”

Notice how the [b] in “bird” causes your vocal cords to vibrate? That’s voiced, while the [ʃ] sound in “shy” is voiceless since there is little to no interference caused by (non-present) vocal cord vibrations.

Classifying Sound

The most basic division of sounds is between the vowels and consonants, but there are also the glides who share properties of both.

Consonants can be either voiced or voiceless but are made with either a complete closure or a narrowing of the vocal tract. You create consonants by blocking or restricting the airflow. Vowels, which are usually voiced, are made without

much obstruction in the vocal tract.

- Note: for all vowels, the tip of your tongue stays down by your lower front teeth.

Vowels also happen to be more sonorous than consonants, and so we perceive them as louder and longer lasting.

Syllables are peaks of sonority— they are surrounded by less sonorous segments. When you count syllables, you are in effect counting vowels, so it can be said that they form the nucleus of a syllable.

| Vowels & syllabic elements |

Consonants & nonsyllabic elements |

|---|---|

| are produced with relatively little obstruction in the vocal tract. |

are produced with a complete closure or narrowing of the vocal tract. |

| are more sonorous. |

are less sonorous. |

Glides can be thought of as rapidly articulated vowels that move quickly to another articulation, like in yet and wet, or like boy and now. These guys never

form the nucleus of a syllable, since they show properties of both consonants and vowels.

Places of Articulation

Each part of the body where you can modify the airstream to produce different sounds is called a place of articulation.

| Place of articulation | Description |

|---|---|

| Bilabial | Both lips come together, as in p, b or m |

| Labiodental | Lower lip touches the upper teeth, as in f or v |

| Dental | The tip of the tongue or just behind it touches the upper teeth, as in th (like in thin or this) |

| Alveolar | Tongue tip contacts the alveolar ridge, as in t, d, n, or l |

| Postalveolar | The area just behind the tip of the tongue contacts the postalveolar region behind the alveolar ridge, as in sh, ch, zh, or j |

| Palatal | Middle of tongue approaches or touches the hard palate, as in y |

| Velar | Back of tongue touches the soft palate (velum) as in k, g, or ng |

| Labiovelar | Back of tongue approaches the soft palate and lips also come close together, as in w |

| Laryngeal | No obstruction anywhere but in the vocal cords, like h |

Manners of articulation

We generally classify our sounds by their manners of articulation— basically how we actually use those articulators. In general, most sounds are egressive, meaning we push air out of lungs to make them, but there are a few examples of ingressive sounds, where we take air into the lungs.

There are glottal stops, where we abruptly bring our vocal folds together and hold them tightly together, as in when you say uh oh! There are voiced sounds, where we vibrate our vocal

folds, like the z in zoo. And then there are voiceless sounds, where we don't vibrate our vocal folds, as in the s in Sam.

But linguists are very finnicky with classifications. So, there's tons of manners of articulations. Here's a few that we definetly use in English.

| Name | What does it do? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stop | It completely stops the airflow. | In [p], you stop the airflow at your lips. In [t], you stop it at your alveolar ridge. |

| Fricative | It constricts the airflow to create friction. | In [f], you make friction between the lips and the teeth. In [s] you make it between the alveolar ridge and the tongue. [f] and [s] are both voiceless, whereas [v] as in vim or [z] as in zoo are voiced fricatives. |

| Nasal | It lets the air flow only through your nose. | In [m], you stop the airflow at the lips while air is going out through your nose. |

| Approximant | It constricts the airflow only a little. | In [j] as in yes, you constrict your vocal tract but the air flows freely. |

| Affricate | It makes a stop and then a fricative. | The first sound in church is the affricate. |

| Vowel | It lets the air flow freely, but you change the sound by changing the shape of the vocal tract with the tongue. | Although I'm sure you know your vowels, just to be sure, they are: a, e, i, o, and u. |

Suprasegmentals

Phones have suprasegmental or prosodic properties, like pitch, loudness, and length.

Pitch allows us to place it on a scale from high to low, and is especially noticeable in sonorous sounds like vowels, glides, liquids, and nasals.

The control of pitch results in tone and intonation.

A language is said to have tone when differences in word meaning are signaled by differences in pitch.

When one says “A car?” with a raising pitch, the word “car” refers to the same thing as when it’s pronounced without that raised pitch; this is intonation. In contrast, a speaker of Mandarin

can say entirely different words by changing the pitch; this is tone. For instance: [mà] with a falling pitch means something entirely different than [má] with a rising pitch.

The amount and classification of tone varies from language to language.

- But.. intonation signals meaning too, right?

- Yes! It does, but it does not change the meaning of a word, rather just signals something different.

- For instance, if I raise my pitch when saying a phrase, it signals that the phrase might be incomplete— teachers and professors do this all the time when they want students to finish their sentences.

- Yes! It does, but it does not change the meaning of a word, rather just signals something different.

Also, it’s worth noting that some languages make use of both intonation and tone at the same time.

Sometimes, vowels are perceived as more prominent than others, like how in “banana” the second syllable is more prominent than the other two. Stress covers the combined effects of pitch, loudness and

length, which gives us this perceived prominence.

Acoustic phonetics

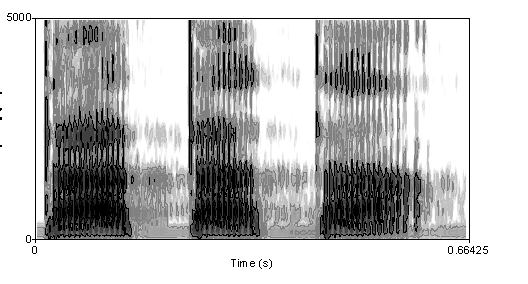

As you can tell from the name, in acoustic phonetics we study the actual physical, acoustic properties of speech sounds. It serves to fundamentally abstract linguistics all the way down to physics. Sometimes, phoneticians use spectrograms of speech to look more deeply into their nature. Obviously, this special subset of phonetics gets very mathy very quickly.

At the most basic level, there are four parts to a sound wave.

The wavelength is the distance between a peaks of waves. It's the horizontal length of one cycle of the wave.

The period is the time it take sto complete one cycle.

The frequency is the number of cycles that pass a set point in a second, usually measured in Hertz (Hz). It's connected to pitch, with higher frequency meaning higher pitch and lower frequency meaning lower pitch.

The amplitude is represented by the height of the waves. Louder sounds have louder amplitudes, and vice versa. It's usally measured in decibels (dB), and the softest sound we can hear is the zero point. We normally speak at 60 dB.

Speech perception

Speech perception deserves an article of it's own, as it's study is deep and storied. It's the process by which sounds are heard, interpreted and understood and plays closely with phonetics and phonology, as well as cognitive science as a whole. It has applications in computer recognition of speech, like in Siri or even Google Translate.

The sound of speech contains acoustic cues that scientists use to differentiate speech sounds belonging to different phonetic categories. One example would be voice onset time, which can signal the difference between voiced and voiceless stops like "b" and "p."

This process is at an intersection of many discplines and is wonderful for demonstrating the interdisciplinary nature of linguistics. In order to understand speech perception, one must draw from cognitive science, linguistics, psychology, and occasionally even computer science.

Sources and resources

| Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction | William O'Grady, John Archibald, Mark Aronoff, Janie Rees-Miller, ISBN-10: 1319039774, ISBN-13: 978-1319039776 |

| Linguistics for Dummies | Rose-Marie A. Déchaine, Eric Vatikiotis-Bateson, Strang Burton, ISBN 1118091698 |

| ELLO course | Universität Osnabrück, Leibniz Universität Hannover, Technische Universität Braunschweig and the University of Göttingen |

| Introduction to Linguistics | Marcus Kracht, University of California, Los Angeles |

| IPA Chart | International Phonetic Association |